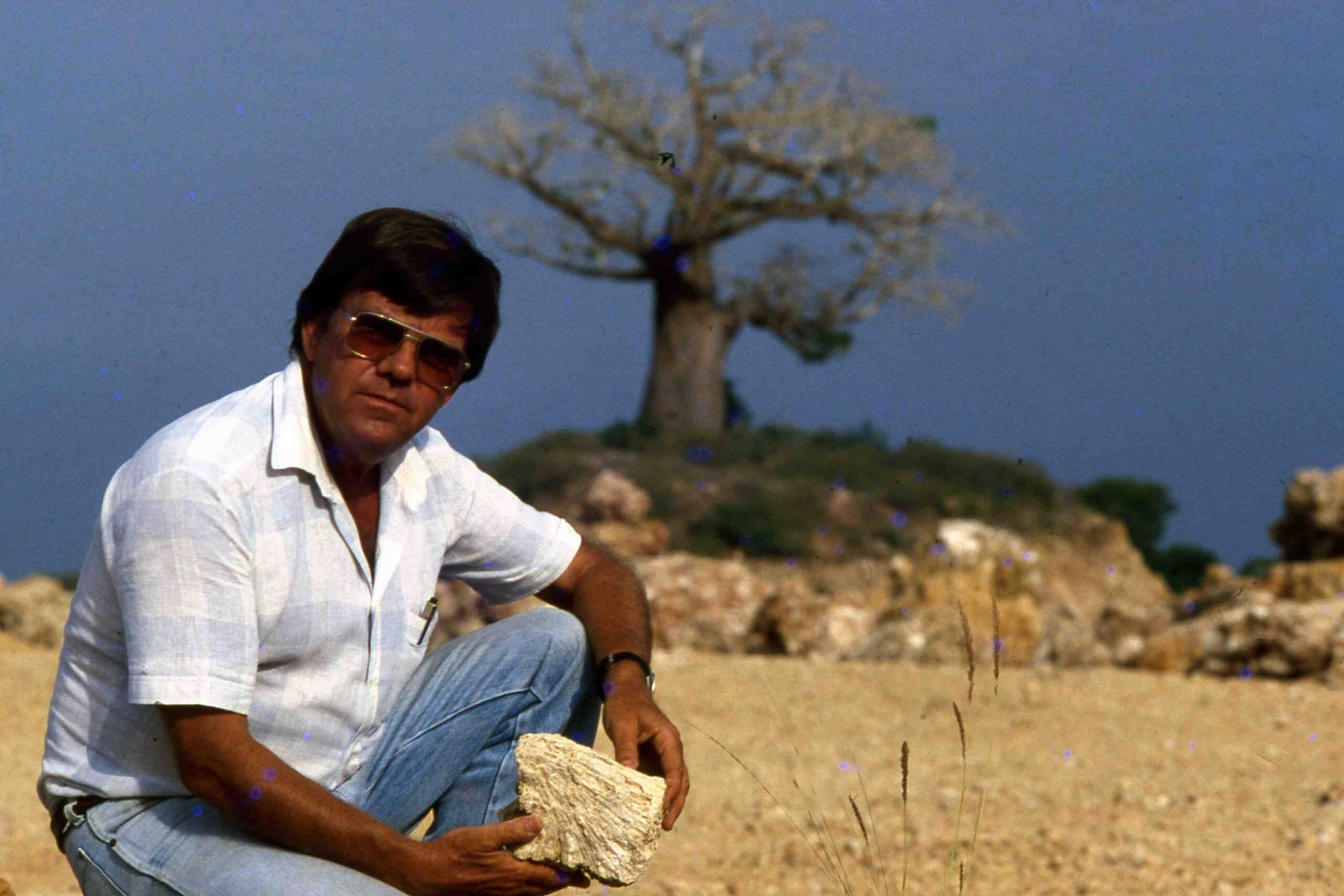

Rene Haller is an ideas man – always experimenting. The exciting thing is that many of his ideas have worked and the results have been spectacular.

He told me that he saw the barren and desolate landscape left by the brutal quarrying of the ancient coral as a challenge. As he walked around the site he would sprinkle the seeds that always filled his pockets. People thought he was crazy to be trying to plant trees in such an inhospitable landscape, but his persistence paid off. In a remote part of the site, he discovered five casuarina trees growing in the rock. It inspired him to plant more – and they grew! The unusual nodules in the roots of the tree provided the nutrients they needed to grow without soil.

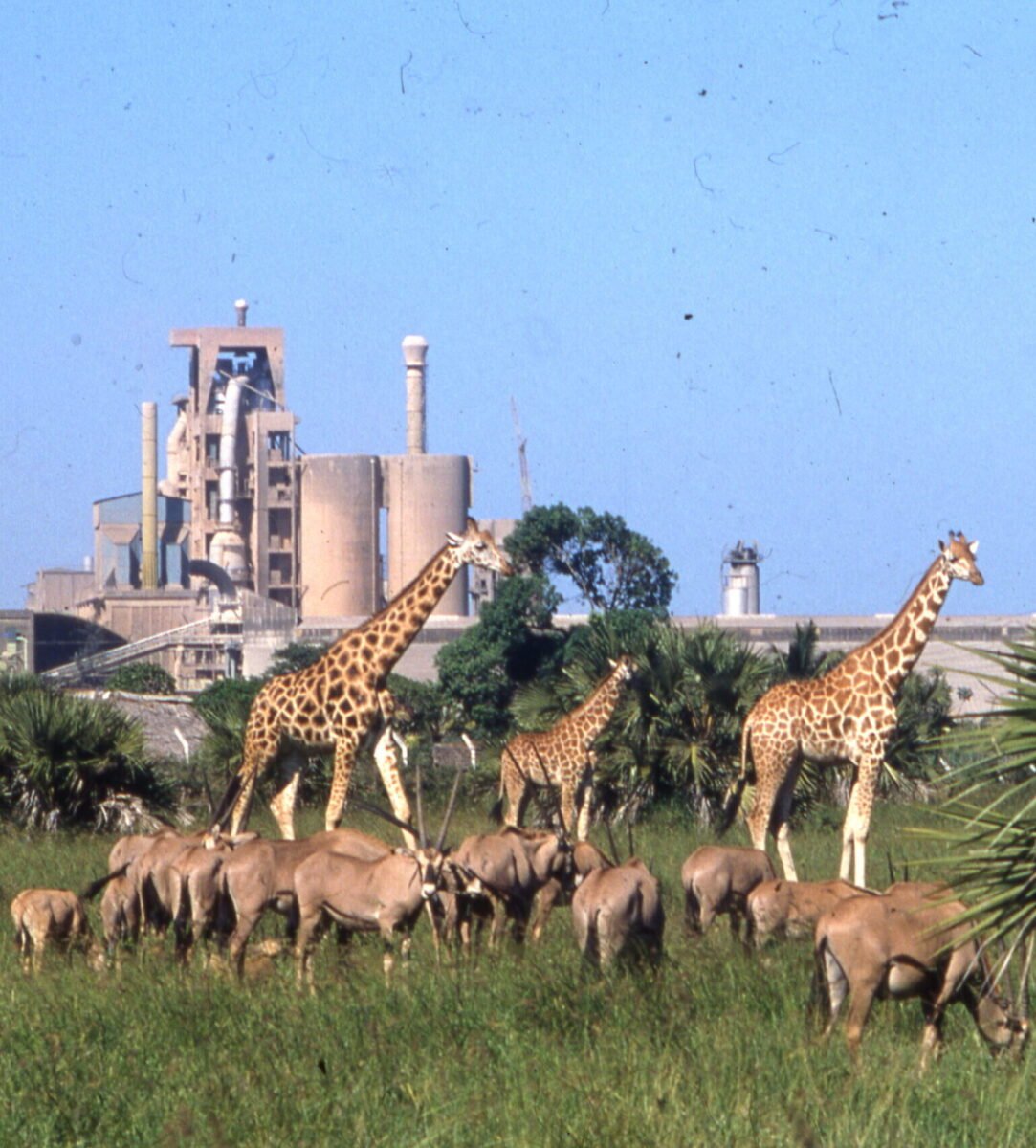

WONDERFUL WILDLIFE HAVE COLONISED

Almost all of these photos were taken by me when visiting Rene at Bamburi.

René’s habit of ‘borrowing’ heavy machinery from the Bamburi Cement Factory without seeking formal permission wasn’t always met with enthusiasm. He used powerful bulldozers and diggers to reshape the barren landscape, crafting pockets of greenery that included islands, terraces, ponds, and forests.

Initially, his ecological initiatives may have seemed like a distraction from the company’s core business. However, his groundbreaking approach to land regeneration, boosting biodiversity, and supporting local communities ultimately gained global recognition. Despite his unconventional methods, René proved to be an invaluable asset, bringing widespread acclaim to the company.

Many years ago, when I first visited the park, Rene showed me a small hut, hidden in the lush green vegetation. it wasn’t significant in itself, but behind it lay an incredible story. He showed me a photo of the hut sitting in a rocky, desert-like moonscape, with no vegetation to be seen. It’s where it all started and the hut was his base. It also became Rene’s refuge and for a while the headquarters of the many micro-enterprises he set up, all based on a living working eco-system.

“In nature there is no waste – it is man’s invention.”

From using the larvae of soldier ants as chicken feed to setting up mini fish farms in urban gardens, his creative approach and off-beat thinking have not only transformed the landscape around Bamburi but the lives of people living there too. What’s more surprising perhaps is that many of the principles that Rene has adopted could be applied anywhere in the world – and that’s what makes it interesting to a wide audience.

Seeing this for the first time, I felt excited. I realised that the principles that Rene applied on the Kenyan coast had the potential to be practised almost anywhere in the world. There were lessons to be learnt, not just in land management but in business too as Rene is adamant that ecology and economy must be in balance.

I first met Rene in 1992 – we were both attending an event honouring our UN Award for Outstanding Environmental Achievement. In Rene’s case, this was just one of many awards he’s received – and I soon understood why.

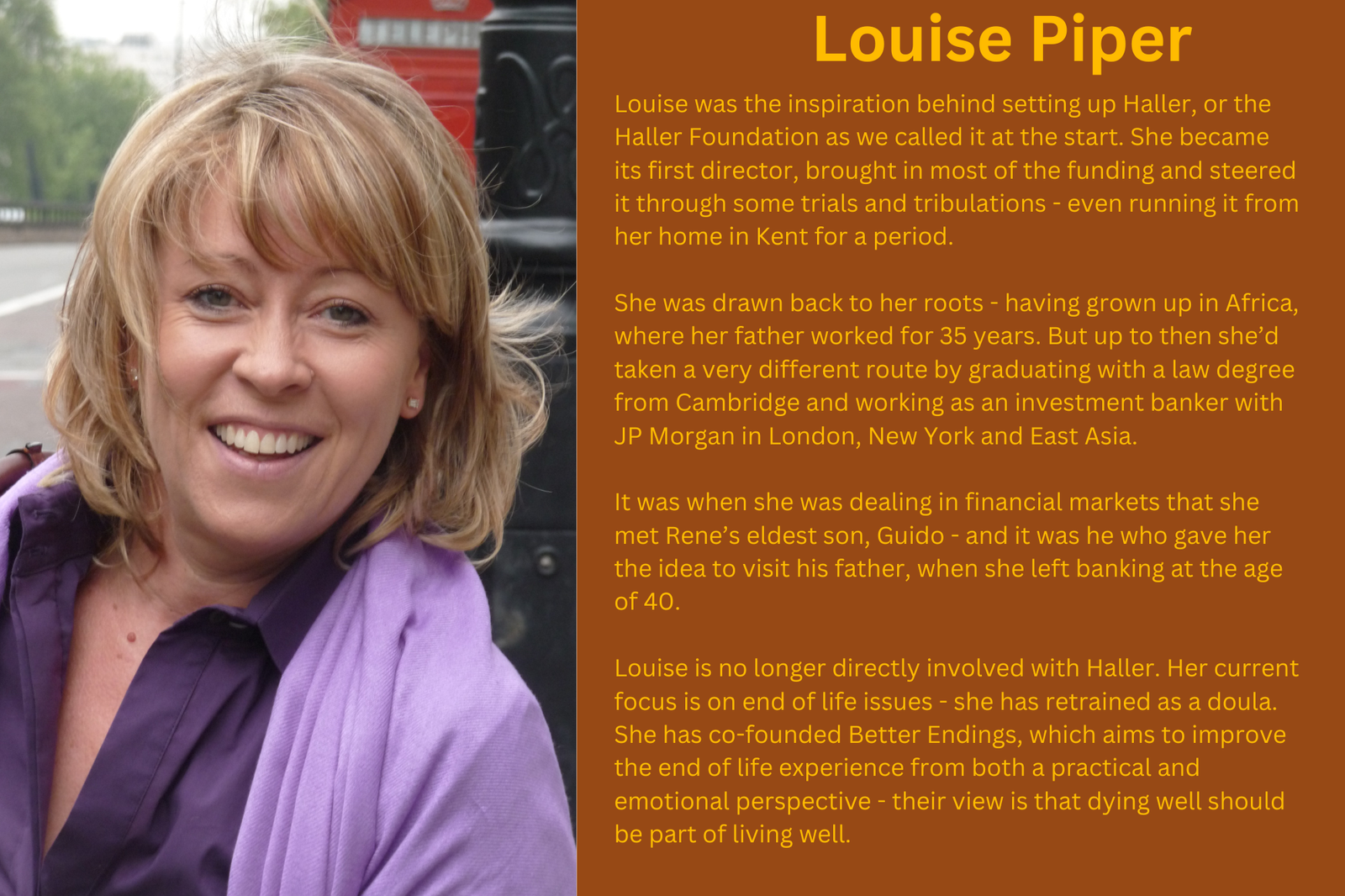

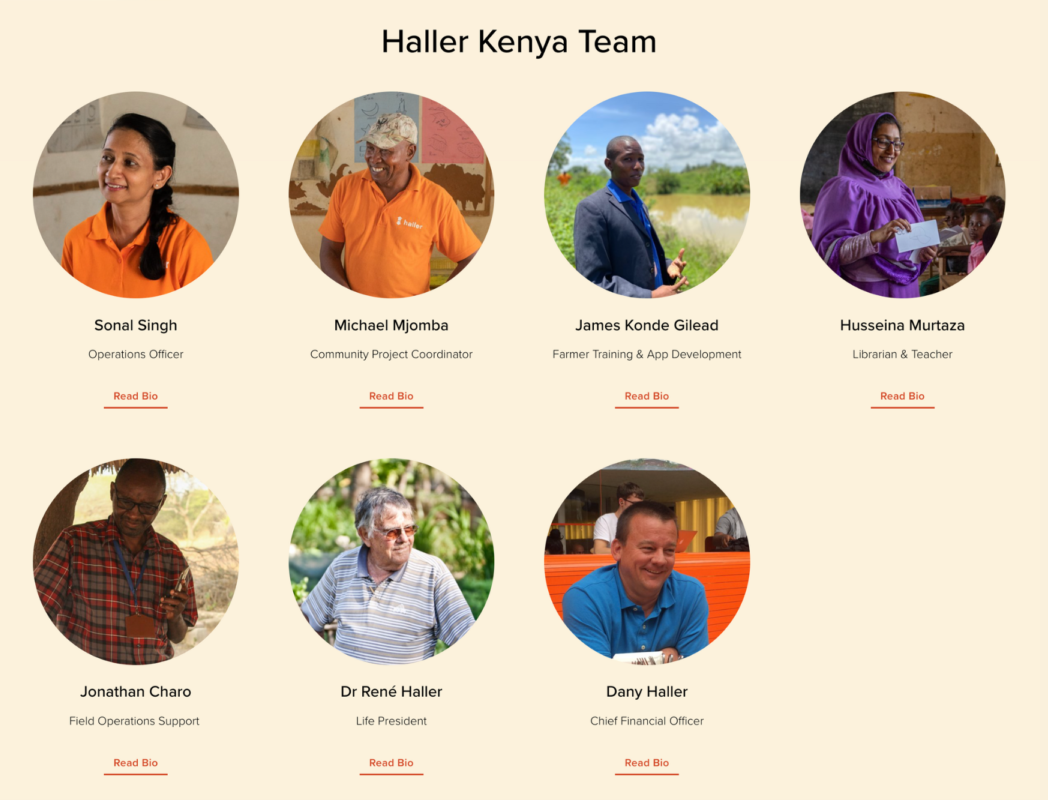

We worked together on several projects and that led Rene to introduce me to Louise Piper. She had been equally inspired by his work and, like me, wanted to ensure that his legacy lived on. Unable to clone Rene we decided that the next best thing was to set up a charity – which we called ’The Haller Foundation’ to raise funds for his work and promote his ideas.

Louise Piper and me in 2004 when we were setting up the Haller Foundation

Since we started in 2004, Haller has set up an award-winning education centre, supported over 60 schools in and around Mombasa, introduced a health clinic, built numerous dams and wells, as well as ran a hugely popular farming training programme, which among other things is helping farmers become self-sufficient and rehabilitate their land.

Louise and I co-founded the Haller Foundation in 2004, but Louise was the main driver in keeping it going.

2011 Haller boarding meeting from left to right: Me – Julia Hailes, Guido Haller (René’s eldest son), Charles Middleton (Chair of Haller from x to x, Dany Haller (René’s youngest son), Louise Piper, Jonathan Ford (Chair of Haller from x to x)

In Kenya, as many readers will know, a lot of trading is done through mobile phones using M-Pesa. A decade after the Haller Foundation was established, the Haller Farmer app was launched in November 2014. The idea was straightforward yet transformative: a practical, interactive resource providing smallholder farmers with accessible, tailored advice on sustainable farming practices.

When René arrived in Africa in 1952, Kenya’s population was around 6 million. Today, it has grown to approximately 56 million, with projections suggesting it will reach 95.5 million by mid-century. During the same period, the population of the African continent is expected to grow more than tenfold, highlighting the immense demographic changes shaping the region.

With the growing demands of more mouths to feed combined with the impacts of climate change, the challenges to come and the need to farm more efficiently and less destructively are going to be even greater than when René set foot on the continent.

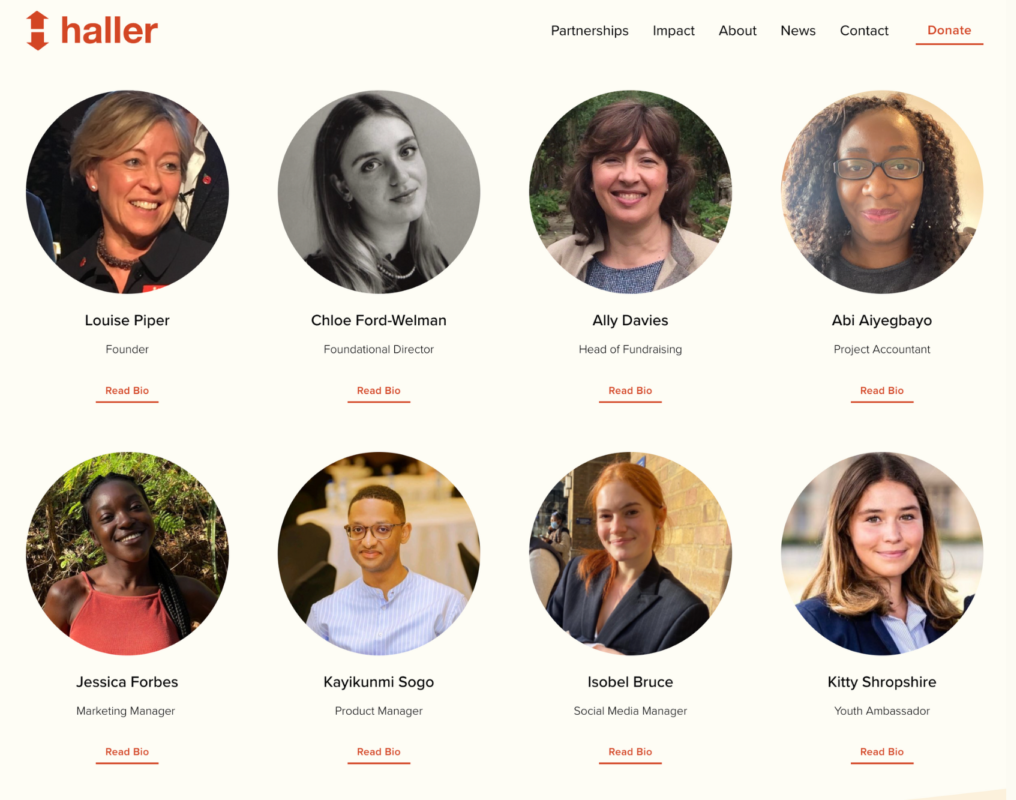

20th ANNIVERSARY OF HALLER

Louise, Rene and me at the 20th Anniversary of Haller – September 2024.

In September 2024 I went to the 20th anniversary of Haller, in London. Amazingly, Rene at 91 was there too. Still energetic, still buzzing with ideas and as always wishing he was back on the Kenyan coast.

Millions of years ago, the landscape surrounding Bamburi was under the sea. Rene has a huge ammonite dating back to that time. Who knows what will happen in the next million years but the record of what Rene has done will forever be part of the story – an ecological legacy that will stand the test of time.